Brown is a faculty affiliate of Africana Studies, the History and Sociology of Science, and the Center for Research on Feminist, Queer, and Transgender Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

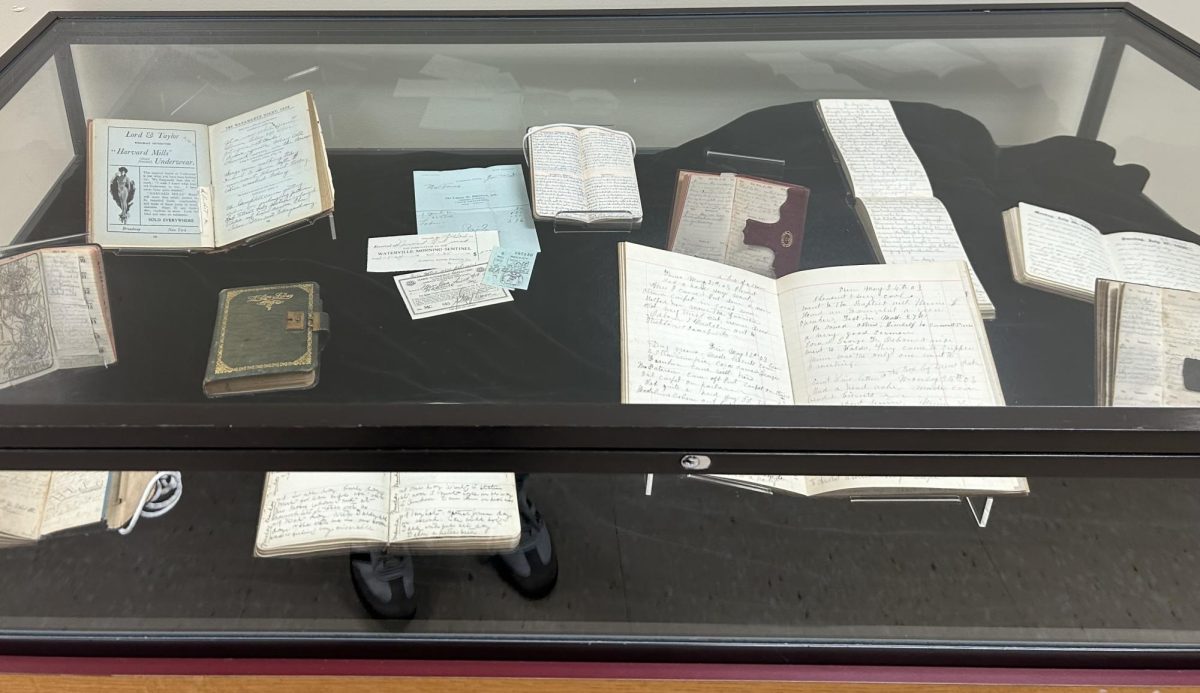

Her book highlights how bodily rights and individual freedoms were put at the center of the abolitionist fight against slavery. Rather than base arguments on abstract rights claims, abolitionists focused on slavery’s direct violation of the health and integrity of the human body, known today as “body politics.” Body politics brought new concepts of ways the physical body could be violated into the debate of what constitutes human rights. Abolitionists argued that family integrity, mother-child relationships, and bodily care had all been violated by slavery.

Abolitionists used the biblical argument of “One Blood,” the belief God made all humans from the same blood, to support their claim that humans are connected. They also used the Law of Blood, jus sanguinis, a principle that states the citizenship of a child is determined by the nationality of one or both parents. These arguments were used to disprove racist science, which believed Black people were characteristically fit, or destined, to be slaves by place of birth. The pursuit for “embodied self-sovereignty,” the belief that people’s bodies were not separate from their rights, by abolitionists was made successful in part by boycotts, the focus of Brown’s lecture.

Brown opens with an impactful poem, “The Slave Mother” by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1854). The poem encapsulates the physical manifestations of an enslaved woman’s entire body in response to her child not being hers. Though she birthed him, and they share blood, he is going to be taken from her and sold. During the abolitionist fight, there was a focus on slavery’s systematic violation of motherhood. The claim was that the ability to shed tears and feel emotional pain was distinctly human and to separate a mother and child transgressed nature. The bodily imagery in poems served to encourage empathy for enslaved mothers and was often written by women themselves.

Abolitionists also encouraged empathy by exposing the pain and oppression responsible for commodities like sugar, tobacco, rice, and cotton through language. Brown explains abolitionists would refer to these products that were considered refined, as being, “stained with blood,” to repel buyers. Abolitionists targeted virtuous women because they couldn’t morally bring goods tainted with sin into their Christian homes.

The boycotts of slave labor created a search for items produced by free labor, which as Brown explains, turned out to be an equally challenging endeavor. Problems of sourcing free labor included poor communication between suppliers and sellers and not enough cash flow for farmers to operate on free labor. Nevertheless, abolitionists continued to recruit, place consumers and households at the center of activism, further their search for technological and agricultural advancements to offset slave labor, and as Brown puts it, “reanimate the connection between the exploited… enslaved producer and the consumer.”

Throughout the lecture, Brown notes that abolitionists were not perfect activists. She states, “significant political work [of the time] was done by people who might not pass our tests for moral purity and anti-racism – they were flawed human beings.” Brown clarifies that though they believed in self-sovereignty, they often held onto anti-black attitudes but nonetheless did important political work. She reminds us, “part of grappling with history as grownups [is] not looking for history as a fairytale to make us feel good about ourselves.”

To watch the entirety of Kathleen Brown’s lecture, or any prior lectures, visit the UNE Center for Global Humanities YouTube channel.