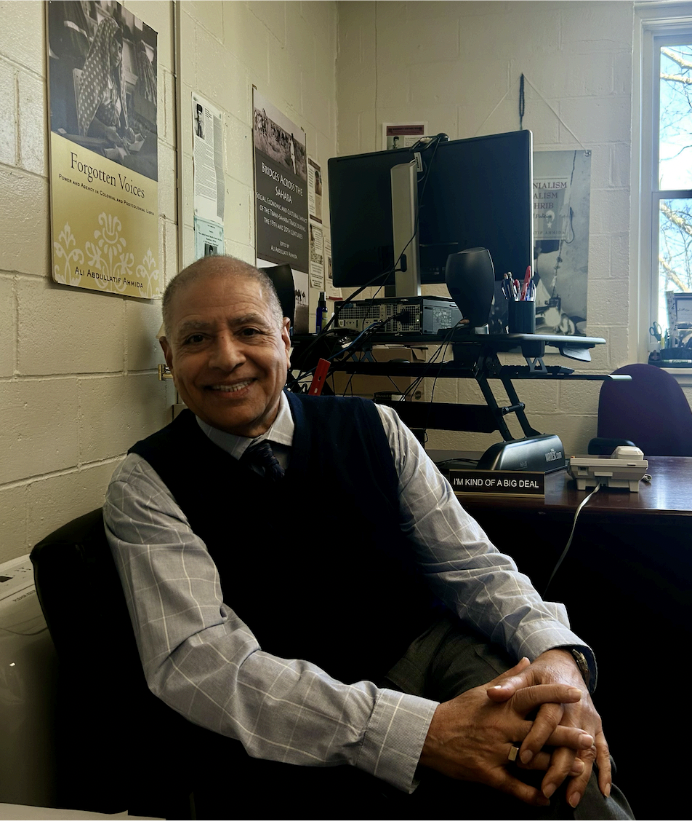

Nestled amidst the rows of doors on the third floor of Decary Hall, located at the University of New England’s Biddeford campus, you will find the unassuming office of Dr. Ali Ahmida.

When Ahmida founded UNE’s Political Science program in 2000, he was already almost a decade into a project, which would continue to expand and impact the greater UNE community for years to come.

“I always try to carry teaching and scholarship as two sides of the same coin. They complement and inform each other – doing the research and writing is linked to my teaching, and my teaching informs my scholarship,” said Ahmida.

“His work is really groundbreaking, and its importance to the larger community of political science academia is massive. His enthusiasm for teaching and advancing his research is what draws students to him and his courses,” said Bella Caprio, senior Marine Affairs and Political Science major who previously worked as a research assistant for Ahmida.

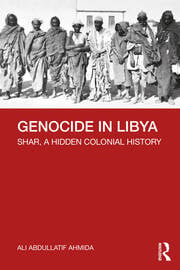

Shar, a Hidden Colonial History

Ahmida’s decades of research began in 1994 with his Ph.D. dissertation on the colonial invasion of Libya and its subsequent reactions. Yet it was his 2020 publication of Genocide in Libya: Shar, A Hidden Colonial History that finally sparked sweeping recognition.

“It took forever! But I couldn’t, in all honesty, hurry something as complex as this,” Ahmida said.

His research, carried out in three languages and spanning three continents, was dedicated to uncovering the genocide of thousands of Libyans during the Italian occupation from the early 20th century, resulting in brutal concentration camps from 1929 to 1934.

“For ten years, I would go [to Libya] every summer after being kicked out of the Italian archives, and one honest historian said to me, ‘Ali, don’t waste your time because they either removed, destroyed, or manipulated archival evidence,’” Ahmida said.

Yet, the countless setbacks proved to be the catalyst for an ingenious new method of research that would set his book and scholarship apart, calling attention to the need for reimagined work.

“The project evolved to become interdisciplinary and employ not only comparative political analysis and political theory of fascism and genocide but also brought in the tools of anthropological and sociological studies of oral history and fieldwork,” he said.

Dr. Susan McHugh, a published writer and professor of English at UNE, has shared many of Ahmida’s objectives in her own research and, as a friend, offered him some insights.

“He has also provided me with much-needed support over the years to believe in the value of untraditional sources and methods in my research. He keeps me true to my roots and is an endless source of inspiration with all of his amazing achievements,” McHugh said.

Reactions varied in the years following the publication of Genocide in Libya: Shar, A Hidden Colonial History, especially from Italian scholars. However, it brought the discussion of this hidden genocide into mainstream scholarship.

“Now people are reexamining not only what happened in Libya but reexamining the Nazi connection I found and keep pushing the envelope and examining dominant scholarship and cannons of modernity and westernized core,” Ahmida said.

Caprio echoed Ahmida’s goal of both interdisciplinary research and teaching as she now works with him, following up on a new lead examining the Nazi presence in Libya.

“His passion and dedication to his research are evident in how he conducts his courses and the themes that he discusses within them. He is a master at tying together difficult and complex topics and delivering information in a digestible way for students to understand,” Caprio said.

While Ahmida’s work has continued to impact the course offerings at UNE and given the small political science department well-deserved credit, the international recognition is, of course, immensely rewarding.

“Above all, I am very happy that it is now reaching a larger academic but also non-academic audience. I was honored in Beirut at the Arab Council of Social Sciences, then in Tunis, I interviewed for a TV show and went to Cairo, where the Egyptian Council of Culture asked me to give a talk on why genocide has contemporary significance,” Ahimda said.

Ahmida’s recognition is ongoing, and looking ahead, there is an opportunity for a full-circle moment following his pursuit of nontraditional methodologies in genocide studies.

“I was invited to participate in four university workshops in Libya across the country, three in the regions where the genocide took place and one in Tripoli,” Ahmida said.

As Genocide in Libya continues to gain more recognition, an additional element of Ahmida’s research has begun to stand out in the discussion.

“[Genocide in Libya is] causing a big uproar and a challenge to our Western Anglo-American scholarship, and it allows the native people to have a voice – which is now, I hope, something to bring to our own American society,” Ahmida said.

Innovative in all aspects, Ahmida’s cross-cultural, cross-societal, and detailed analysis reveals the consequences of knowledge that has been hidden and controlled.

“At the end, even though it took longer, I managed to recover the mystery of the genocide that has been forgotten for almost 70 years,” Ahmida said.

This article was written in the Spring of 2024. Bella Caprio has since graduated.