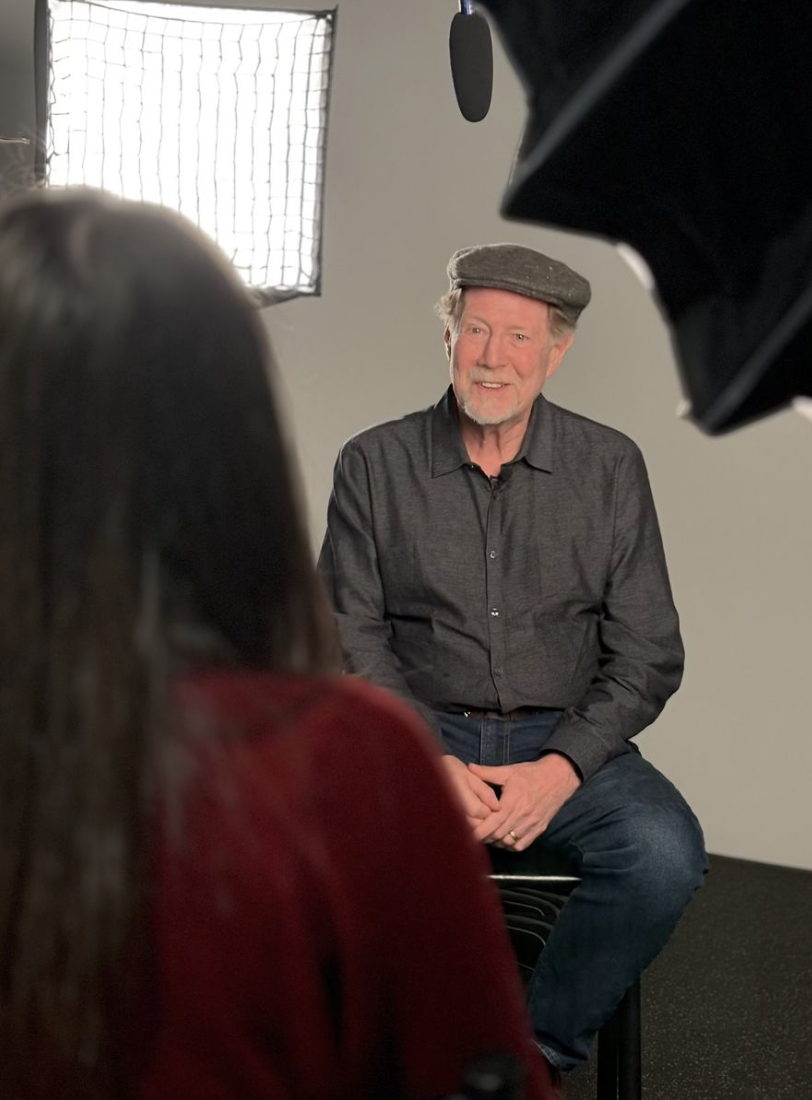

With help from The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit news outlet in Maine, filmmaker Rick Goldsmith has been traveling through the state of Maine to shed light on a growing crisis in American Journalism: local newspapers across the country are being bought up and gutted by hedge funds.

The University of New England hosted an interview with Goldsmith in the new Nor’Easter Production studio, along with a screening of the documentary in ACHS.

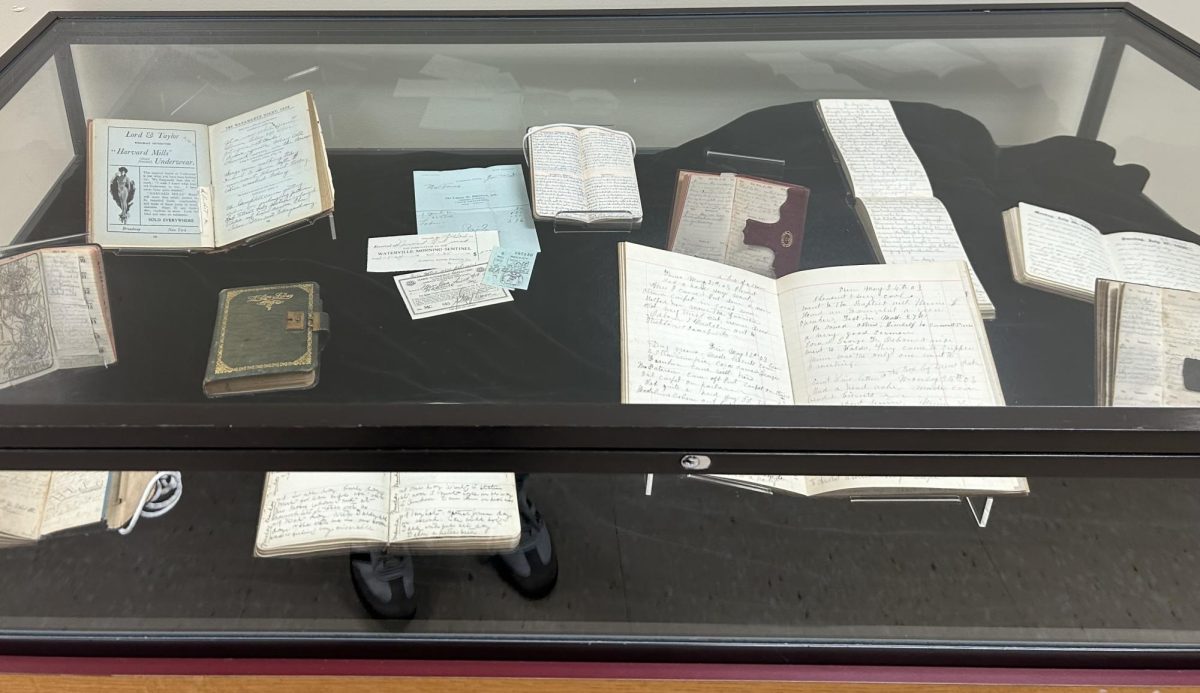

In the interview, Goldsmith explained how he began work on the documentary in 2018 after reading an editorial in The Denver Post highlighting the problem. This article came directly from the Post’s editorial team, calling out the large hedge fund that had purchased the Post as a way to inform the public of what was happening in the industry.

“There was a rebellion of sorts in journalism,” said Goldsmith in reference to the article and subsequent protests spearheaded by journalists across America. The film documents the timeline of the ongoing fight against hedge funds up until 2022.

“The events started happening one after another in front of my eyes,” said Goldsmith, who stated that he had to stop himself from continuing to record for the film; otherwise, it would have never gotten done.

Hedge funds like Alden Global Capital, the firm focused on in the film and purchaser of the Denver Post, buy companies that are doing poorly financially and sell off valuable assets such as real estate in a strategy called distressed asset investing.

“It’s like an old automobile that’s basically junk,” explained Goldsmith in an interview with UNE students. “It doesn’t start, but you have the radio. That’s worth something.”

According to the documentary, hedge funds targeted newspapers because of the failure of the newspaper business model to adapt to new technology in the early 2000s.

“No one’s making money in news,” said Jo Easton, Director of Development at Bangor Daily News. Many of the papers bought by hedge funds end up with reduced staff or closing entirely.

While Maine has not been targeted by major hedge funds specifically, local papers are still feeling the pressure. According to the Executive Director at The Maine Monitor, Micaela Schweitzer-Bluhm, up to 60 percent of newsroom jobs in the state have been lost. This is in addition to the creation of two “news deserts,” areas with no local papers, situated in Waldo and Somerset counties.

Much of the film’s later half is devoted to inventing a new model for journalism in the 21st century.

“To those who think we’ve lost the battle, that’s just wrong,” said Goldsmith. One such effort is to shift daily news into a public service model similar to how a fire department operates. “You pay for the police department. They aren’t making money off it. Fire department? You pay for it,” he said.

“There is no model for journalism as a commercial business,” said Schweitzer-Bluhm during a Q&A segment after the film’s showing.

According to Easton, much of the funding for local news comes from state-level governments, primarily in the form of tax credits. While there was initial hesitation from journalists, many have started to welcome the idea as a way to keep corporate greed away from newspapers.

Future screenings of Stripped for Parts can be found on the production company’s website here: https://kovnocommunications.org/films/stripped-for-parts/

The Maine Monitor is an independent news organization dedicated to offering free investigative journalism and keeping Mainers informed.